In questo breve articolo, pubblicato sul New York Times, Paul Krugman sostiene che la realtà di oggi conferma che Londra ha fatto la scelta giusta non aderendo all’Euro.

Questi i due benefici principali:

1) possedere una propria banca centrale di ultima istanza per la protezione dei debiti sovrani;

2) la svalutazione interna per rilanciare la competitività dell’economia. La Gran Bretagna ha ottenuto risultati importanti dalla svalutazione della sua moneta che in paesi come la Spagna si sarebbero potuti raggiungere solo al prezzo di una prolungata disoccupazione di massa.

Conclude Krugman: i sostenitori integralisti dell’euro non vogliono ammettere che la moneta unica sia stata una pessima idea dal punto di vista della teoria economica, con l’aggravante che di fronte ad ogni problema i paesi ed i leader non riescono mai a trovare soluzioni condivisi efficaci. E nonostante sia evidente ormai il fallimento dell’Euro, ci sono paesi, come la Polonia che ancora pensano di aderirvi. Si può comprendere che tornare alle monete nazionali non sia allo stato un’impresa facile, ma perché pensare di entrare nell’Eurozona proprio ora, quando si è avuta la fortuna di sottrarsi al disastro?

Rationality and the Euro

di Paul Krugman

Simon Wren-Lewis, for once, has a happy story to tell. He looks back at Britain’s fateful decision, ten years ago, not to join the euro, and argues that the decision was made on the basis of — gasp! — actual analysis. Gordon Brown (who deserves a much better rap than he gets) brought in real economic experts, who used a real economic framework — optimum currency area theory — and concluded that the case for euro membership was not good.

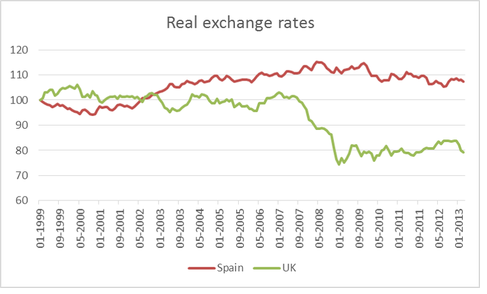

And boy, was that a good call; despite the best efforts of Osborne and Co. to mess it up, there’s no comparison between British woes and those of other European nations that had large capital inflows and housing booms. Partly this is because of the De Grauwe point, which was imperfectly grasped in 2003 — the crucial importance of having your own central bank as lender of last resort for sovereign borrowing. But it’s also largely because of a point that was perfectly well understood in 2003 and has been confirmed by experience: “internal devaluation”, reducing relative prices with a fixed exchange rate, is really hard compared with just devaluing your currency. Here are BIS estimates of the Spanish and UK real exchange rates, 1999-01 = 100:

Notice how Britain effortlessly achieved a real depreciation that, if it’s possible at all, will take years and years of mass unemployment in Spain.

Unfortunately, Wren-Lewis’s description of an actual rational decision process is all too rare — perhaps especially when it comes to the euro. Talk to euro advocates and they cannot entertain, even as a hypothetical proposition, the notion that the single currency was a bad idea; I came away from one talk with the clear message that the euro cannot fail, it can only be failed, that any problems simply show that countries and leaders lack sufficient nobility of purpose.

And despite the overwhelming evidence that the euro was an even worse idea than it appeared 10 years ago, countries — notably Poland — are still considering joining. I understand that leaving the euro is a very difficult thing to contemplate; but getting in now, when you had the great good luck to avoid this mess? Awesome.

Fonte New York Times

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/06/rationality-and-the-euro/

ScenariGlobali.it Scenari globali, l'approfondimento in rete delle notizie di attualità politica,economica, culturale, sportiva ed altro.

ScenariGlobali.it Scenari globali, l'approfondimento in rete delle notizie di attualità politica,economica, culturale, sportiva ed altro.